The current issue of The American Harp Journal includes a wonderful article by Melina van Leeuwen entitled SALZEDO’S NEW HARPISM. Of particular interest is his elimination of rests as a compositional principle for harp.

This is really an important idea for harpists. Rests, unless we intentionally dampen a string, do not accomplish silence on harp and so, to add them is superfluous and makes interpreting the music more difficult. Especially for those most familiar with music written by harpists, we simply don’t see them scattered though our music in the way they are for keyboard or other instruments.

According to van Leeuwen, there are six idiomatic principles of which to be aware, the first of which is the “omission of rests unless needed for rhythmic clarity”. As the resonance is the main character of harp that separates it aurally from piano, it is also the reason rests in music hold less significance to the performer.

It’s been my frustration, when doing work for hire, that in editing by the publisher, they sometimes “take the harp out” and “insert too much piano” and as I read this article, it occurred to me that most of the disagreement comes on this issue, the harpistic approach vs. the pianistic approach. Each is helpful for its own idiom.

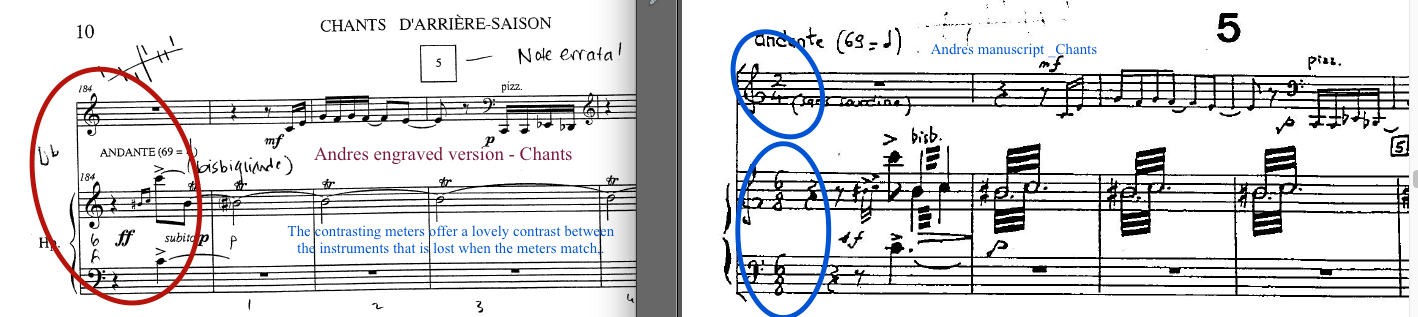

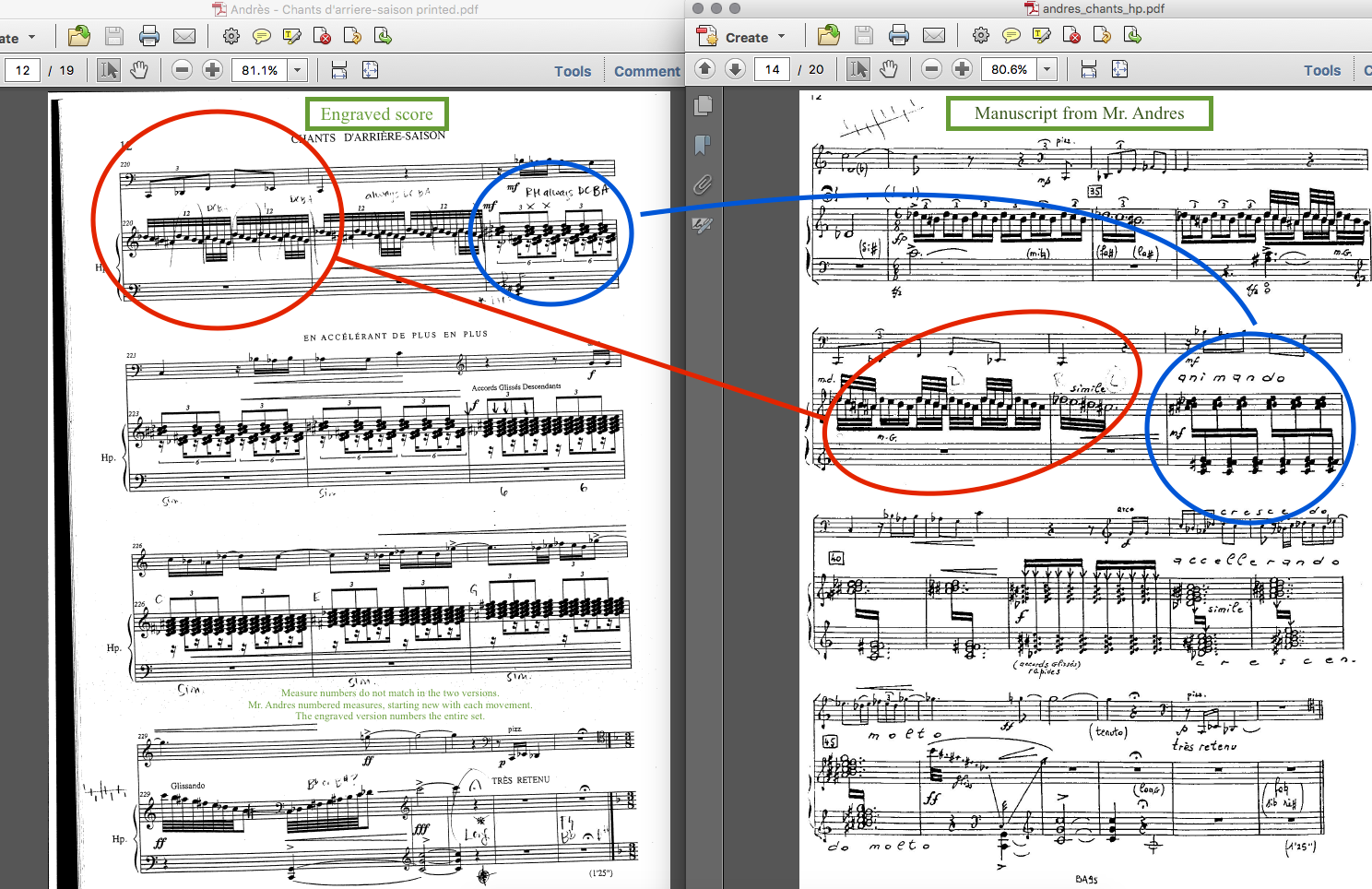

Bernard Andrés has expanded on beautiful notationfor harp, and a study,especially of his manuscript shows his careful choices in notation. Not only his lack of unnecessary rests, but his use of beaming in CHANTS D’ARRIERE-SAISON (harp and cello or bassoon, or horn) makes the difference between the piece being very close to sight readable (though difficult) and the need for assessment of the structure. I use this piece as an example only because the music was issued in both manuscript (shown on the right) and an engraved edition (shown on the left).

In a rare turn of events, the manuscript of this score is easier by far to read than the engraved edition, which also, sadly, contains a large number of errata. I’ve not had contact with a harpist performing the piece since 2016 when Colleen Potter Thornburn and Delaine Leonard helped sort out the new edition against the manuscript and recordings. See examples below and more in the article in the Harp Journal.

A copy of the errata sheet (complied by Barbara Ann Fackler and Colleen Potter Thornburn of Orange Apple Pair, with a later update from Delaine Leonard), can be downloaded with this link. If you know that corrections have been made, I'd appreciate that info as well.

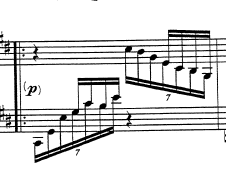

Movement 6: The meter here is 3/8, eighth note = 138.

The beaming of the notes in the manuscript (image on the right) simplifies reading both placement and rhythmic structure by beaming entire measures as a group. This is especially helpful at this tempo. The orignal notation of Mr. Andres also simplifies the melody notes in the treble notationally to see that the melody functions as a hemiola over the rest of the pattern.

Notice that there are rests in the engraved edition (left) but not in the manuscript (right). Also, note the notes in the bass clef and compare between the two notational choices: the simplified notation on the right wouldn't work for piano, as they wouldn't know to hold that first octave longer, but it's going to do that on harp unless it's damped, so the example on the right is suits harp well.

Movement 7: The meter is 2/4, quarter note = 72

The cross staff beaming in the manuscript (image on the right), makes it very quick to see the most efficient way to finger this, without brackets or fingerings. At a glance, I can see where I need to reach and how things fit.

The step directions in the manuscript offer information for fingering in a way that the engraved version does not.

Notice that there are rests in the engraved edition (left) but not in the manuscript (right).

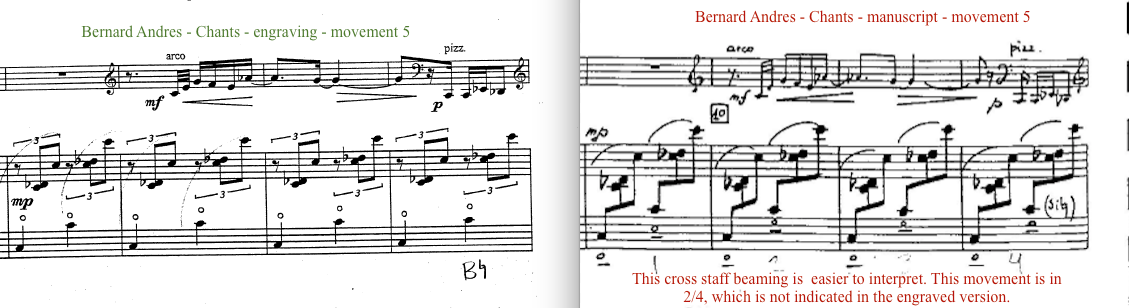

Movement 5:meter is 2/4 in the solo instrument and 6.8 in the harp part, quarter note = 69

The meter is not correctly marked in the manuscript, this is listed in the errata sheet.

Cross staff beaming streamlines interpretation, both rhythmically and in placing, fingering included. There's far less to ponder as groups are easily detected. By using "simile" for repeated patterns, interpretation of the music is also simplifed.

In the example marked in red, note that the harpist who used this score needed to indicate where left hand was used, while in the manuscript, it was obvious from notation.

Also note, in the last system, theren's an example of errata, the hold is in the original manuscript version, but was missing in the engraving. Also, at this point, Mr. Andres did not indicate a specific end note for the gliss, but the engraved version does. The chord in the left hand at that point offers a nice final end point for the gliss without needing to take care to end at a specific pitch, truly more harpist friendly.

Movement 5: meter is 2/4 in the solo instrument and 6/8 in the harp part, quarter note = 69

Again, the cross staff beaming that Andres uses makes interpretation of both placement and rhythmic structure easily identifiable.

Movement 5: meter is 2/4 in the solo instrument and 6/8 in the harp part, quarter note = 69

The bisbigliando is easier to read than the trill, especially reiterated every measure

The time signatures for this movement are missing entirely in the engraved version. The manuscript invites marking the downbeat with each new measure, helping to maintain the rhythmic structure in a way the tied note does notes do not.

In the original version, the solo instrument is in 2/4 and the harp in 6/8.

The original was much easier to read. Perhaps a small difference to the ear, but a lovely difference none the less to the conversation between instruments.